Hotelling's T^2 in Julia, Python, and R

The t-test is a common, reliable way to check for differences between two samples. When dealing with multivariate data, one can simply run t-tests on each variable and see if there are differences. This could lead to scenarios where individual t-tests suggest that there is no difference, although looking at all variables jointly will show a difference. When a multivariate test is preferred, the obvious choice is the Hotelling’s \(T^2\) test.

Hotelling’s test has the same overall flexibility that the t-test does, in that it can also work on paired data, or even a single dataset, though this example will only cover the two-sample case.

Background

Without delving too far into the math – Wikipedia has a more thorough look at it – if we have two samples \(X\) and \(Y\) pulled from the same normal distribution, then the test statistic will be

$$ t^2 = \frac{n_x n_y}{n_x+n_y} (\bar{X} - \bar{Y})^T \Sigma^{-1} (\bar{X} - \bar{Y}) $$

where \(n_x\) is the number of samples in \(X\) (same for \(n_Y\)), \(\bar{X}\) is the vector of the column averages in \(X\) (same for \(\bar{Y}\)), and \(\Sigma\) is the pooled covariance matrix. This follows a \(T^2\) distribution, which isn’t among the distributions typically found in statistical software. But it turns out that this can be made to follow an F-distribution by multiplying by the right factor:

$$ \frac{n_x + n_y - p - 1}{p(n_x + n_y - 2)} t^2 \sim F(p, n_x+n_y-p-1) $$

where \(p\) is the number of variables in the data. The F-distribution is much more commonplace, so this should be much easier to deal with.

Since computing the statistic and p-value requires nothing beyond some linear algebra and probability distributions, it’s not too difficult to implement. Thorough implementations of Hotelling’s \(T^2\) aren’t hard to find, though from what I’ve seen it’s usually in a package that’s not standard or common – Python seems to lack one in its major statistics libraries while Julia and R have them as parts of specific libraries (HypothesisTests and ICSNP respectively). But since these aren’t too difficult to code, this post will code the two-sample test manually in all three languages. I checked my results against the ICSNP library’s test to ensure that things were working correctly.

The Data

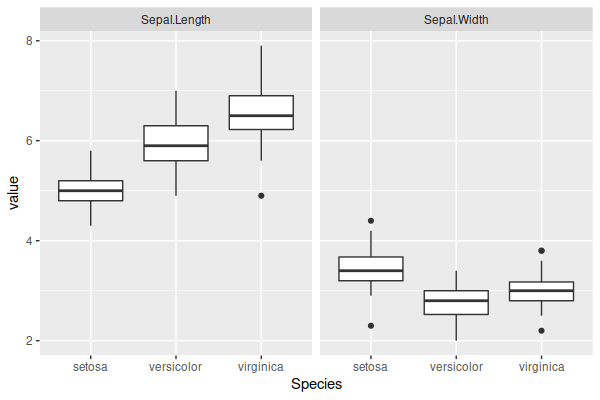

For data, we’ll use the sepal measurements in the iris dataset. Looking at the data, there are definite differences between the classes, and while there is an extension of Hotelling’s test that can handle more than two samples, we’ll just use the Versicolor and Virginica species. From the plot below, there does appear to be some difference, and univariate t-tests on each variable strongly suggest that significant differences exist.

The reason for only using the sepal measurements and those two species is because some other combinations were producing p-values small enough that Julia rendered them as zero, especially when all four variables were used. So I picked something that produced a p-value that all three languages could properly display.

R Implementation

R probably has the most straightforward implementation, in that all of the tools needed to write this are actually imported upon starting up, so no external dependencies exist. I am using the glue library, but that’s just for formatting the output of print(), so it’s not necessary for computing results.

library(glue)

TwoSampleT2Test <- function(X, Y){

nx <- nrow(X)

ny <- nrow(Y)

delta <- colMeans(X) - colMeans(Y)

p <- ncol(X)

Sx <- cov(X)

Sy <- cov(Y)

S_pooled <- ((nx-1)*Sx + (ny-1)*Sy)/(nx+ny-2)

t_squared <- (nx*ny)/(nx+ny) * t(delta) %*% solve(S_pooled) %*% (delta)

statistic <- t_squared * (nx+ny-p-1)/(p*(nx+ny-2))

p_value <- pf(statistic, p, nx+ny-p-1, lower.tail=FALSE)

print(glue("Test statistic: {statistic}

Degrees of freedom: {p} and {nx+ny-p-1}

p-value: {p_value}"))

return(list(TestStatistic=statistic, p_value=p_value))

}

data(iris)

versicolor <- iris[iris$Species == "versicolor", 1:2]

virginica <- iris[iris$Species == "virginica", 1:2]

TwoSampleT2Test(versicolor, virginica)

## Test statistic: 15.8266009919182

## Degrees of freedom: 2 and 97

## p-value: 1.12597832539986e-06 Julia Implementation

Julia is a little bit trickier. It might be because I haven’t gone too deep into it, but Julia seems a little less casual about type conversions than R, so there is a need to mindful of those. In particular, the matrix multiplication step goes smoothly but returns a 1-by-1 array instead of a single numeric value like R does, so the statistic needs to be extracted from the array. There are also a few packages that need to be installed and imported, though these aren’t very unusual ones.

using Distributions

using RDatasets

using Statistics

function TwoSampleT2Test(X,Y)

nx, p = size(X)

ny, _ = size(Y)

δ = mean(X, dims=1) - mean(Y, dims=1)

Sx = cov(X)

Sy = cov(Y)

S_pooled = ((nx-1)*Sx + (ny-1)*Sy)/(nx+ny-2)

t_squared = (nx*ny)/(nx+ny) * δ * inv(S_pooled) * transpose(δ)

statistic = t_squared[1,1] * (nx+ny-p-1)/(p*(nx+ny-2))

F = FDist(p, nx+ny-p-1)

p_value = 1 - cdf(F, statistic)

println("Test statistic: $(statistic)\nDegrees of freedom: $(p) and $(nx+ny-p-1)\np-value: $(p_value)")

return([statistic, p_value])

end

iris = dataset("datasets", "iris")

versicolor = convert(Matrix, iris[iris.Species .== "versicolor", 1:2])

virginica = convert(Matrix, iris[iris.Species .== "virginica", 1:2])

TwoSampleT2Test(versicolor, virginica)

## Test statistic: 15.826600991918198

## Degrees of freedom: 2 and 97

## p-value: 1.1259783254669031e-6The results appear to be the same, although there is a very slight difference in the p-values, on the order of \(10^{-16}\) or so. I don’t know whether that’s an implementation detail or something else. The way Julia handles its arrays is a little different as well, since we’re taking the transpose of δ in the right-side multiplication instead of the left side.

Also, if you’re not familiar with Julia, the use of the Unicode character for the Greek letter delta (δ) might be surprising. Julia actually can use Unicode characters for variable names, which is pretty neat (though not generally advisable, I think).

Python Implementation

This one is probably the most convoluted of the three, though even it isn’t that bad. We again require a couple of fairly common packages. There are two major differences in the Python code compared to the previous languages:

- The dataset isn’t loaded as a dataframe, but instead as an object of type

sklearn.utils.Bunch, with properties that contain the variables and the target class. - Matrix operations aren’t quite as native to Python, so we lack an operator for performing it and have to use

np.matmul()twice as a result.

import numpy as np

from sklearn import datasets

from scipy.stats import f

def TwoSampleT2Test(X, Y):

nx, p = X.shape

ny, _ = Y.shape

delta = np.mean(X, axis=0) - np.mean(Y, axis=0)

Sx = np.cov(X, rowvar=False)

Sy = np.cov(Y, rowvar=False)

S_pooled = ((nx-1)*Sx + (ny-1)*Sy)/(nx+ny-2)

t_squared = (nx*ny)/(nx+ny) * np.matmul(np.matmul(delta.transpose(), np.linalg.inv(S_pooled)), delta)

statistic = t_squared * (nx+ny-p-1)/(p*(nx+ny-2))

F = f(p, nx+ny-p-1)

p_value = 1 - F.cdf(statistic)

print(f"Test statistic: {statistic}\nDegrees of freedom: {p} and {nx+ny-p-1}\np-value: {p_value}")

return statistic, p_value

iris = datasets.load_iris()

versicolor = iris.data[iris.target==1, :2]

virginica = iris.data[iris.target==2, :2]

TwoSampleT2Test(versicolor, virginica)

## Test statistic: 15.82660099191812

## Degrees of freedom: 2 and 97

## p-value: 1.1259783253558808e-06We have a third, slightly different p-value than both previous implementations. Again, I don’t really know what’s going on.

Conclusion

So writing a Hotelling’s \(T^2\) test yourself isn’t too hard. These functions could be generalized to handle one-sample, paired, and other variants as well if desired; this should prove to be a good start if so.