Hangman and Conditional Probability

A while ago, I heard an episode of Freakonomics Radio which discussed games and strategies for playing them. It stuck to pretty simple games, so there were no excursions into game theory or such, but the part about Hangman caught my interest. Discussions in that part largely amounted to the use of conditional probability – since you know something about the word you’re trying to guess, you might be able to come up with a better strategy than blind guessing or just guessing based on the frequency of letters in the English language.

Code for this was written in Python.

Hangman

The game itself is fairly simple: you’re given a word or phrase and you guess one letter at a time. If the letter is in the text, instances of that letter are filled in; if it’s not in the word, part of a hanging stick figure is drawn. You win if you complete the text before the stick figure is completed.

Since you have feedback on the text, it’s possible to go for various approaches to guessing. A very simple strategy could be trying letters in order of their frequency in the language, without regard to anything else. Or you could just try a few of the most common letters first and coming up with better guesses afterwards, in something analagous to the final round on Wheel of Fortune. There is also the possibility of using the length of the words as information to refine your guesses more quickly (though I doubt this would work as well except for fairly short words).

The version I’m simulating here is a little different, as it just lets you guess until you complete the word (though we can get the winning scenarios later) and it only ever uses one word at a time, but the core remains the same. As far as strategies go, I opted for three different strategies:

- Guess based on the most common letter (that hasn’t already been guessed) in the whole set of words.

- Guess based on the most common letter (that hasn’t already been guessed) among words of the same length.

- Guess based on the most common letter (that hasn’t already been guessed) among words of the same length and that are consistent with the letters that have already been found.

A fourth strategy could be a tweak of the third strategy which would eliminate of words containing guesses that did not appear in the goal word; unfortunately, at the time I thought of this, the code was far enough along that adding this strategy would require notable structural changes to the code, so I did not do this.

The only remaining thing is that the definition of “most common letter” is a bit vague. The definition I’ve heard the most is “appears the most in a large amount of typical English writing,” but that’s trickier to define for the conditional natures of the second and third strategies. So for each of the above strategies, I’m testing with two different definitions of “most common”:

- The one that appears the most number of times in the word list.

- The one that appears in the largest fraction of words in the word list.

The second definition doesn’t fit the typical definition of “most common” as well as the first, but it may be nicer in the case of Hangman since you’re penalized purely on the number of wrong answers and safer-but-still-correct guesses could be easier with this tactic.

I used the word list from here, which contains about 370,000 unique words that lack punctuation. There are plenty of words in there which appear to be foreign loanwords, however, or foreign words without direct analogues in English.

Code

The first step in coding this was to determine what the best way to hold the solution was. Since strings are immutable in Python, you can’t make a solution string and (neatly) substitute characters into the string as needed. I decided on using a list of one-character strings where:

- The length of the list was equal to the length of the word.

- “.” was the initial value for each one-character string.

An advantage of this is that it allows for a neat solution to finding words that match the known letters – just use "".join() on the list and you end up with a regular expression that will match words of that pattern since “.” is the regex wildcard character.

So, package imports first:

from collections import Counter #for easy counting of letters in some cases

import re

from string import ascii_lowercase

from tqdm import tqdm #purely to track execution progress; not necessaryA function for finding the indices of a letter in the goal word:

def indices_in_word(letter, goal_word):

"""Get indices of a letter in a word."""

indices = []

i = goal_word.find(letter)

while i != -1:

indices.append(i)

i = goal_word.find(letter, i+1)

return indicesThen a class for holding the word list and performing the needed filtering of the word lists:

class HangmanWordList:

def __init__(self, full_word_list):

self.full_word_list = full_word_list

self.valid_words = full_word_list

def reset_word_list(self):

"""

Return valid_words to contain all words in the list. Needed for

when the same HangmanWordList is reused on consecutive games.

"""

self.valid_words = self.full_word_list

def filter_valid_words_by_length(self, length):

"""

Removes entries from valid_words that don't match the specified

length (should be the length of the goal word).

"""

self.valid_words = [w for w in self.valid_words if len(w) == length]

def filter_by_known_letters(self, solution_list):

"""

Removes words that don't match the pattern

"""

solution = "^" + "".join(solution_list) + "$"

self.valid_words = [w for w in self.valid_words if re.match(solution, w)]

def most_common_letter_by_count(self, used_letters=[]):

"""

Return the list of letters not in used_letters, ordered by

the number of appearances they have in valid_words.

"""

all_words_string = ''.join(self.valid_words)

all_words_letter_count = Counter(all_words_string)

for l in used_letters:

all_words_letter_count.pop(l, None)

return all_words_letter_count.most_common()

def most_common_letter_by_words(self, used_letters=[]):

"""

Return the list of letters not in used_letters, ordered by

the fraction of entries in valid_words that they appear in.

"""

possible_letters = [l for l in ascii_lowercase if l not in used_letters]

letter_in_word_freq = {l:sum([1 for w in self.valid_words if l in w]) for l in possible_letters}

return Counter(letter_in_word_freq).most_common()The biggest caveat with this class is the most_common_letter functions. In the case where there’s a tie for the most common letter, it’s up to Python’s internals which letter comes first, but I couldn’t think of a good way to score those situations, so I’ve just left it alone.

Originally, an instance of this class was meant to be the primary object passed around in computation, resetting the word list at the start of each attempt at a solution and going through the process of filtering and determining next letters every time. However, this proved to be extremely slow, to the point where attempting to cover the entire word list would have taken several days on my machine. Some experimenting indicated that the functions for finding the most common letters were the biggest time sinks. As a result, I ended up precomputing as many of the most common letter lists and word lists as I could.

with open("words_alpha.txt", "r") as f:

words = f.readlines()

words = [w.strip() for w in words]

words = [w for w in words if 20 >= len(w) >= 3]

word_list = HangmanWordList(words)

CASE_1_LETTERS = word_list.most_common_letter_by_count()

CASE_4_LETTERS = word_list.most_common_letter_by_words()

CASE_2_LETTERS = {}

CASE_5_LETTERS = {}

for l in range(3,21):

word_list.filter_valid_words_by_length(l)

CASE_2_LETTERS[l] = word_list.most_common_letter_by_count()

CASE_5_LETTERS[l] = word_list.most_common_letter_by_words()

word_list.reset_word_list()

## cases 3 and 6 can only get initial word lists precomputed

CASE_3_6_WORD_LISTS = {}

for l in range(3,21):

CASE_3_6_WORD_LISTS[l] = HangmanWordList([w for w in words if len(w) == l])Cases 1, 2, and 3 refer to the three strategies listed earlier – use all words, use words of the same length, use words of the same length and pattern – with “most common letter” defined by the frequencies of the letters in the words. Cases 4, 5, and 6 are the same but determining the most common letter by the percentage of words it appears in; since they’re only minor tweaks of the first three cases, their code is not reproduced below.

## CASE 1: guess on full corpus, most common by count of all letters

def case_1_game(goal_word):

solution = ["."] * len(goal_word)

guesses = []

while "." in solution:

next_guess = CASE_1_LETTERS[len(guesses)][0]

if next_guess in goal_word:

letter_indices = indices_in_word(next_guess, goal_word)

for li in letter_indices:

solution[li] = next_guess

guesses.append(next_guess)

return guesses

## CASE 2: guess on words of same length, most common by count of all letters

def case_2_game(goal_word):

solution = ["."] * len(goal_word)

guesses = []

while "." in solution:

next_guess = CASE_2_LETTERS[len(goal_word)][len(guesses)][0]

if next_guess in goal_word:

letter_indices = indices_in_word(next_guess, goal_word)

for li in letter_indices:

solution[li] = next_guess

guesses.append(next_guess)

return guesses

## CASE 3: guess on words of same length & pattern, most common by count of all letters

def case_3_game(goal_word, word_list):

word_list.reset_word_list()

solution = ["."] * len(goal_word)

guesses = []

while "." in solution:

word_list.filter_by_known_letters(solution)

next_guess = word_list.most_common_letter_by_count(guesses)[0][0]

if next_guess in goal_word:

letter_indices = indices_in_word(next_guess, goal_word)

for li in letter_indices:

solution[li] = next_guess

guesses.append(next_guess)

return guessesThen running the games is fairly easy.

guess_tuples = []

for w in tqdm(word_list.full_word_list):

guesses1 = case_1_game(w)

guesses2 = case_2_game(w)

guesses3 = case_3_game(w, CASE_3_6_WORD_LISTS[len(w)])

guesses4 = case_4_game(w)

guesses5 = case_5_game(w)

guesses6 = case_6_game(w, CASE_3_6_WORD_LISTS[len(w)])

guess_tuples.append((w, len(guesses1), len(guesses2), len(guesses3),

len(guesses4), len(guesses5), len(guesses6)))The reason for storing them in tuples that the ultimate goal is to store them in a dataframe, and the tuples make that easy:

hangman_df = pd.DataFrame.from_records(guess_tuples)

hangman_df.columns = ["Word", "Case1Guesses", "Case2Guesses", "Case3Guesses",

"Case4Guesses", "Case5Guesses", "Case6Guesses"]

hangman_df["WordLength"] = [len(w) for w in hangman_df["Word"]]

hangman_df["UniqueLettersInWord"] = [len(set(w)) for w in words]

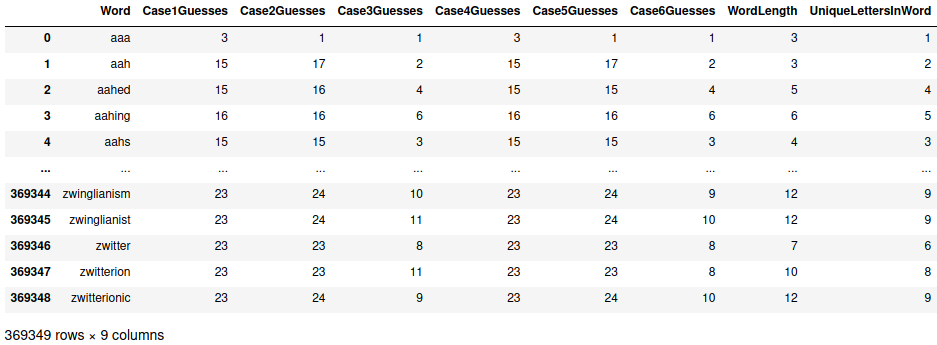

While it’s not a detailed look at the data, we can already see that there may not be huge improvements going from “guessing by most common in all words” (cases 1 & 4) to “guessing by most common in words of same length” (cases 2 and 5), but there does seem to be some significant improvement when using the known letters to guess (cases 3 and 6).

With our dataframe now set, we can start asking questions. (For brevity and clarity, the analysis code will not be repeated here, but is present in the linked Jupyter notebook.)

Question 1: Does the “most common” method make a difference?

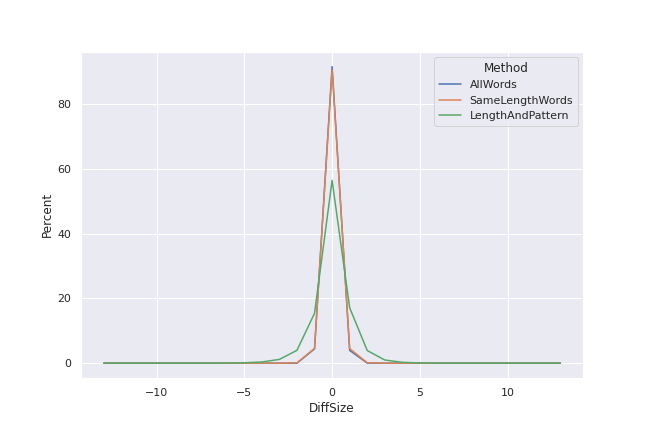

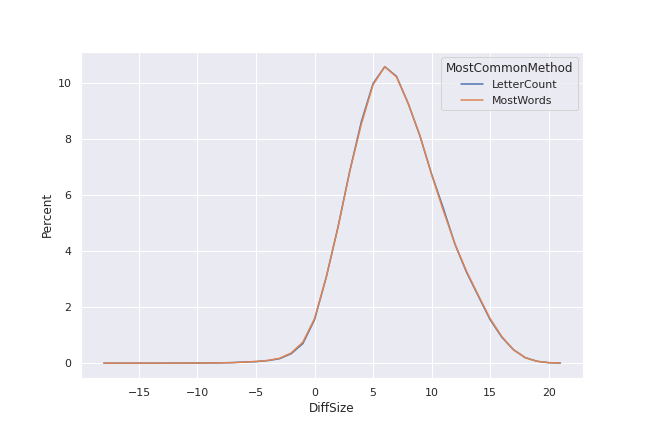

A casual check of the differences between the number of guesses for each “most common” method suggests there’s not much difference unless you’re using filtering your word list by pattern:

Over 90% of the words in the list have no difference in the number of guesses when either looking at all words or just considering words of the same length, and only a tiny amount of the remainder differ by more than 1 in either direction. If you start filtering on length and pattern, there are a lot more words that differ by some amount, up to 13 guesses in isolated cases. But very few go beyond a three-guess difference, and over half of the words still use the same number of guesses.

Strictly speaking, these results should probably be split up by the word length, as while you may be able to get shorter words in only a couple of guesses, the number of unique letters in longer words will prevent that and change the possibilities somewhat. However, considering how little the number of guesses changes for most words in this case, that didn’t seem to be useful.

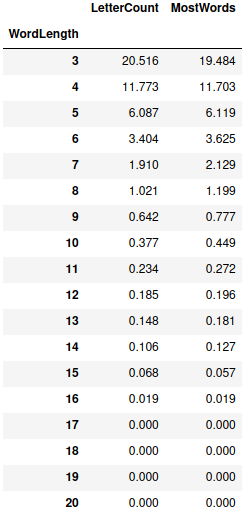

Question 2: How much does filtering by word length improve the number of guesses over checking all words?

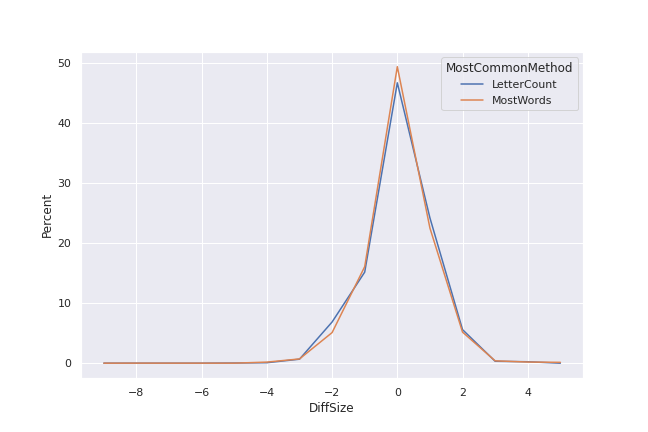

The counts here are the number of guesses for the “use full word list” case minus the number for the “use words of same length” case. Nearly half of the words require the same number of guesses for both “most common” selection methods, and few have differences of more than two guesses.

I’m somewhat surprised by how many words have their number of guesses increase. It’s a smaller number than those that require fewer guesses – the number goes down in about 30% of words and goes up in around 20% – but I would have expected the number of words needing more guesses to be quite a bit smaller.

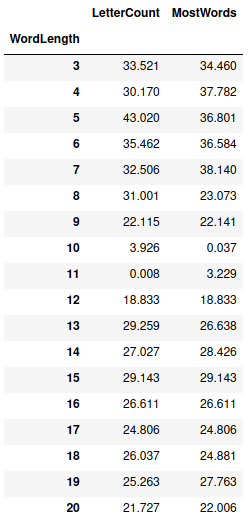

The table below lists the percentage of words that require more guesses, broken down by word length. There’s a weak tendency towards shorter words requiring more guesses, but it’s present across almost every word length:

Perhaps it’s just that a full word list contains more words with uncommon letters than expected – I know that I had to look up ‘zwitterion’ when I saw it in the dataframe view earlier in the post (it’s from chemistry).

Question 3: How much does filtering by word length and pattern improve the number of guesses compared to filtering only on word length?

Considering patterns as well appears to be a much improved guessing strategy, however:

Less than three percent of the words require as many or more guesses when filtering on pattern is added. Repeating the percentage-needing-more-guesses-by-word-length check above, it looks like the vast majority of words that do require more guesses are only a few letters long.

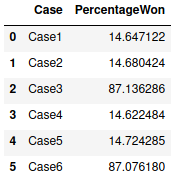

Question 4: For each case, how many words would each case win on?

This is a little vague since I don’t know of any hard rule on the number of wrong guesses it takes to lose. My personal experience suggests six – one for the stick figure’s head, one for the body, and one for each limb.

We know both the number of guesses and the number of unique letters in each word, the latter of which is equal to the number of correct guesses, so we can get the number of wrong guesses by subtraction. Then we just see how many words have no more than 5 wrong guesses (it’s five since if you make a sixth wrong guess, the game ends before you can make the remaining correct guesses).

As expected, there are many more words you can win on if you filter by pattern (cases 3 & 6). It’s actually a little shocking how big of a swing that is.

Conclusion

If you want to improve your guesses in Hangman, just condition your next guess based on what the most likely letter is given the letters you already know – the method of choosing which letter is most likely didn’t matter much in this case. To be fair, I expect that this is more or less the typical strategy already used, but it’s interesting to see how big of an effect it has.