Depression Preprint Analysis, Part 2

This is the second post in a series that is looking at a collection of preprint papers on a specific topic – in this case, depression. In the previous post, I went through and scraped the website of the Open Science Foundation (OSF) for a list of preprints on the topic. As it turned out, the majority of preprints that dealt with the psychological condition were from PsyArXiv, so I’m focusing this post on topic modeling using only preprints from there.

Scraping PsyArXiv

The code underlying PsyArXiv appears to be negligibly different from the code underlying the OSF searach, so the scraping code for the search doesn’t change appreciably. However, this time around, we’re also concerned with accessing the individual pages for two additional things:

- Tags for describing the content. These may be given by the uploader – at the very least, they don’t seem as regular, given differences in capitalization and some seemingly over-specific tags. It’s not clear if this is useful, but I grab it nonetheless.

- The preprints themselves. This is mostly easy, as the download URL is just the preprint URL with “/download” appended to it, though there is one catch: preprints can come in three different file formats – PDF, DOC, and DOCX. Thankfully, there is a filename on the page itself which gives that information.

Collecting the search data, I find a total of 905 results (in mid-August 2021), somewhat more than the 696 that turned up in the OSF search. I’m not certain why that is, though I would trust the number of results from PsyArXiv itself versus an aggregator.

Examining the Preprints

However, we end up with many fewer then 905 usable preprints. Some weren’t actually downloaded due to having pages on PsyArXiv despite being ultimately withdrawn – I had a total of 764 papers downloaded, and upon inspection of the files, 100 turned out to be duplicates, in that they have the same file size and same title save the presence of a colon in some of the titles. A couple of examples (duplicates on the left, non-duplicates on the right):

Another five that had non-English title and content were removed, leaving 659 in total.

Since there are three different file formats to deal with, I’m using the textract library, which acts as an abstraction layer for reading several different file formats. Reading in the files, unfortunately, yields 48 preprints that throw errors when trying to read them in, leaving 611 preprints to analyze.

>> import os

>> import re

>>

>> import pandas as pd

>> import textract

>> from tqdm import tqdm

>>

>> preprints = os.listdir("preprints/")

>>

>> fails = 0

>> doc_list = []

>> good_titles = [] # useful later

>> for p in tqdm(preprints):

>> try:

>> doc_list.append(textract.process(f"preprints/{p}").decode())

>> good_titles.append(p)

>> except:

>> fails = fails+1

>>

>> fails

48Topic Modeling with Latent Dirichlet Allocation

To get a sense of major topics for the papers, I’m employing Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA). Much of my code is based off of an example in the scikit-learn documentation, though with several additions and modifications.

To start with, LDA requires a term frequency matrix to compute its results, which can be found using the CountVectorizer in scikit-learn.

>> import re

>>

>> from nltk import word_tokenize

>> from nltk.stem.snowball import SnowballStemmer

>> import pandas as pd

>> from sklearn.feature_extraction.text import CountVectorizer

>> from sklearn.decomposition import LatentDirichletAllocation

>>

>> STEMMER = SnowballStemmer("english")

>>

>> def custom_tokenizer(document):

>> tokens = word_tokenize(document)

>> tokens = [t for t in tokens if re.match("[a-zA-Z]", t)]

>> tokens = [STEMMER.stem(t) for t in tokens]

>> return tokens

>>

>> n_features = 1000 ## number of terms to keep

>> n_components = 10 ## number of topics

>>

>>

>> tf_vectorizer = CountVectorizer(max_df=0.75,

>> min_df=3,

>> max_features=n_features,

>> tokenizer=custom_tokenizer,

>> ngram_range=(1,2))

>> term_frequencies = tf_vectorizer.fit_transform(doc_list)

>> lda = LatentDirichletAllocation(n_components=n_components, max_iter=10,

>> learning_method='online',

>> random_state=0)

>> lda_topics = lda.fit_transform(term_frequencies)Some notes on the above:

- Without using the

tokenizerortoken_patternarguments (which lets you specify a regex that tokens have to match),CounterVectorizerwill attempt to match everything it could, including numbers. That’s a problem with this data, since citations mean that four digit years and numbered references are all over the preprints, which is part of the reason for the custom tokenizing function above. - The other reason for the tokenizing function is that, while inspecting the most important terms in the output, it was clear that a lot of them were just slight variations on the same word, like “adolescent” vs “adolescence” or “dependent” vs “dependence.”

- The syntax for

max_dfandmin_dfis interesting – if you supply a value less than 1, it’s interpreted as the fraction of documents in the dataset, but an integer greater than 1 is interpreted as a count of documents. So the values used here mean “terms which appear in at least three but less than 75% of the documents.” - No stopwords were used were used here due to the below warning which popped up. It seems that the tokenizing (and hence, in this case, the stemming) occurs before the stopword check, and scikit-learn warns against stopwords being tokenized to something that isn’t actually in the list of stopwords. I’ve tried to counter the issue by setting the maximum document frequency somewhat lower than I would have otherwise.

/home/me/.local/lib/python3.8/site-packages/sklearn/feature_extraction/text.py:383: UserWarning: Your stop_words may be inconsistent with your preprocessing. Tokenizing the stop words generated tokens [‘abov’, ‘afterward’, ‘alon’, ‘alreadi’, ‘alway’, ‘ani’, ‘anoth’, ‘anyon’, ‘anyth’, ‘anywher’, ‘becam’, ‘becaus’, ‘becom’, ‘befor’, ‘besid’, ‘cri’, ‘describ’, ‘dure’, ‘els’, ‘elsewher’, ‘empti’, ‘everi’, ‘everyon’, ‘everyth’, ‘everywher’, ‘fifti’, ‘forti’, ‘henc’, ‘hereaft’, ‘herebi’, ‘howev’, ‘hundr’, ‘inde’, ‘mani’, ‘meanwhil’, ‘moreov’, ‘nobodi’, ‘noon’, ‘noth’, ‘nowher’, ‘onc’, ‘onli’, ‘otherwis’, ‘ourselv’, ‘perhap’, ‘pleas’, ‘sever’, ‘sinc’, ‘sincer’, ‘sixti’, ‘someon’, ‘someth’, ‘sometim’, ‘somewher’, ‘themselv’, ‘thenc’, ‘thereaft’, ‘therebi’, ‘therefor’, ‘togeth’, ‘twelv’, ‘twenti’, ‘veri’, ‘whatev’, ‘whenc’, ‘whenev’, ‘wherea’, ‘whereaft’, ‘wherebi’, ‘wherev’, ‘whi’, ‘yourselv’] not in stop_words.

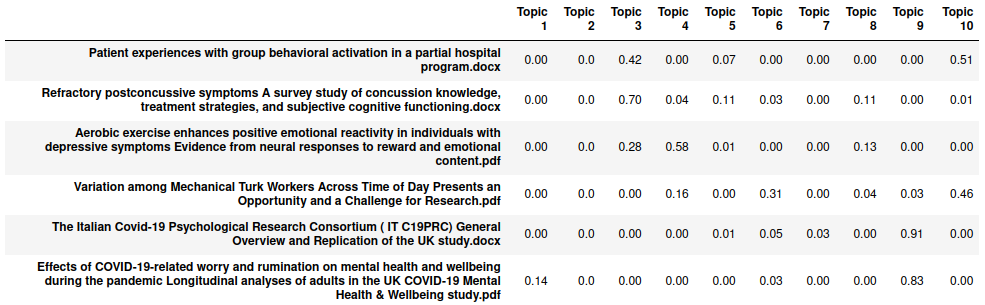

We can look at the topics in the papers in a couple different ways. The fit_transform step returns a sparse NumPy array of the topics weightings per document, which can be visualized a bit better with a dataframe:

>> lda_topic_df = pd.DataFrame(lda_topics.round(2), columns=[f"Topic {x}" for x in range(1,11)], index=good_titles)

>> lda_topic_df.head(6)

Each row in the dataframe is normalized to have the contents sum to 1, with the values in the individual columns being the weights of the topics. We can also visualize the most common n-grams frequencies per topic, using a function from the example in scikit-learn documentation:

>> import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

>>

>> ## function copied verbatim from sklearn docs

>> def plot_top_words(model, feature_names, n_top_words, title):

>> fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 5, figsize=(30, 15), sharex=True)

>> axes = axes.flatten()

>> for topic_idx, topic in enumerate(model.components_):

>> top_features_ind = topic.argsort()[:-n_top_words - 1:-1]

>> top_features = [feature_names[i] for i in top_features_ind]

>> weights = topic[top_features_ind]

>>

>> ax = axes[topic_idx]

>> ax.barh(top_features, weights, height=0.7)

>> ax.set_title(f'Topic {topic_idx +1}',

>> fontdict={'fontsize': 30})

>> ax.invert_yaxis()

>> ax.tick_params(axis='both', which='major', labelsize=20)

>> for i in 'top right left'.split():

>> ax.spines[i].set_visible(False)

>> fig.suptitle(title, fontsize=40)

>>

>> plt.subplots_adjust(top=0.90, bottom=0.05, wspace=0.90, hspace=0.3)

>> plt.show()

>>

>> plot_top_words(lda, tf_vectorizer.get_feature_names(), 15, "Topics")

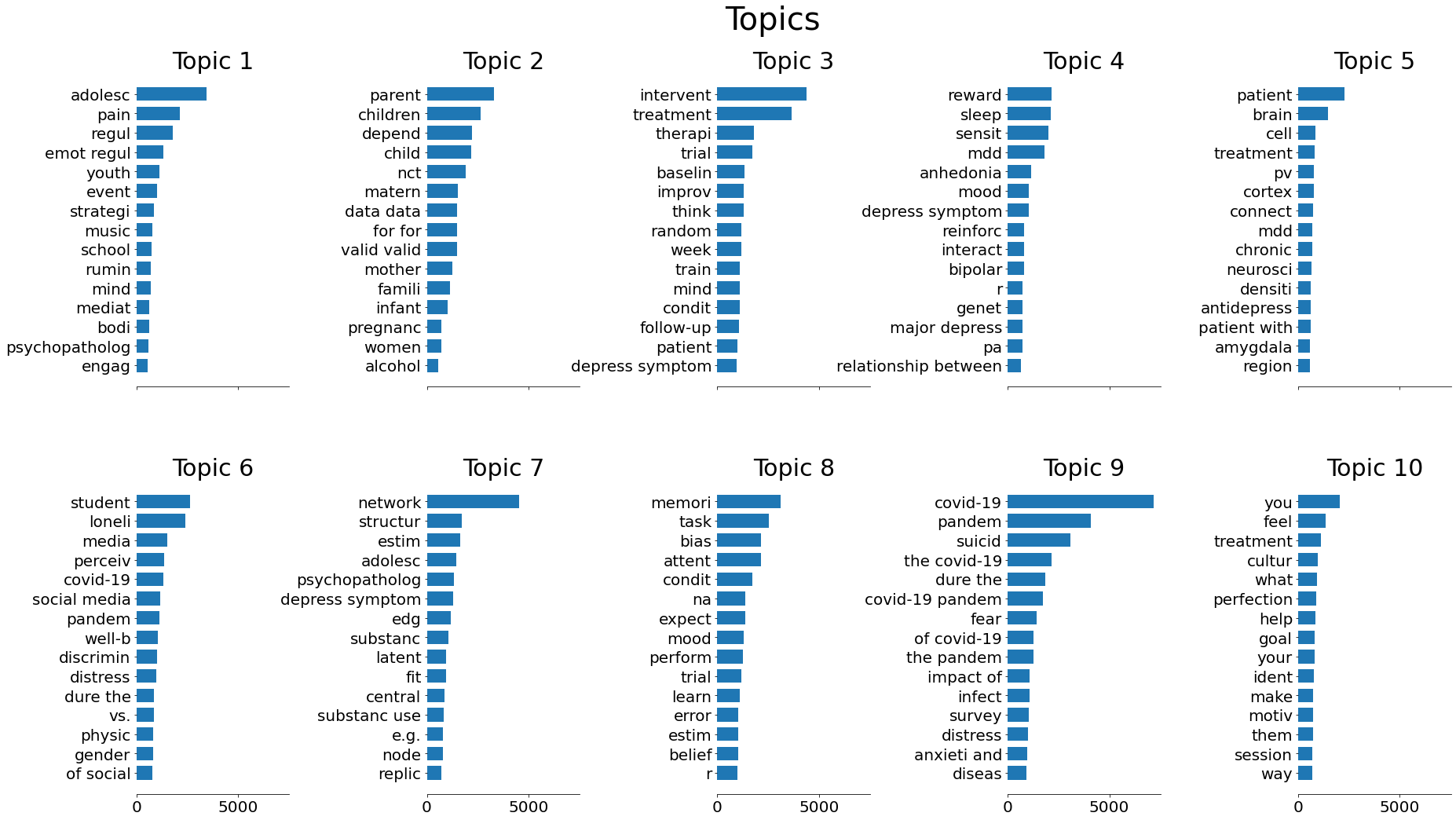

With some supplemental checks of the highest values for each topic in the dataframe (not reproduced here), we can examine the individual topics.

Topic 1 appears to deal mostly with emotional regulation and/or adolescence, given the five most frequent terms. Most of the top 10 preprints (in terms of topic score) cover both in their titles, such as “Emotion regulation in response to daily negative and positive events in youth: The role of event intensity and psychopathology”, so this seems pretty clear.

Topic 2 is largely about depression in the context of pregnancy and infancy to early childhood, either in terms of postpartum depression for the mother or attempting to find predictors of depression later in the child’s life.

The exception to this is a preprint titled “Network analyses reveal which symptoms improve (or not) following an Internet intervention (Deprexis) for depression”, which has the highest score (1.00, second highest was 0.60) in this topic. Inspection of the preprint suggests its prominence is because it contains dozens of pages of output from R code which outputs the phrase Note: NCT for dependent data has not been validated a large number of times – presumably, definitions of “dependent” were conflated.

Topic 3 covers an assortment of interventions and other theraputic strategies, such as “Autobiographical memory-based intervention for depressive symptoms in young adults: A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-reminiscence therapy”. Several cover smartphone- or otherwise Internet-powered intervention strategies, something that would probably fit Topic 2’s outlier much better.

It seems like Topic 4 is a bit of a mixed bag. The two most common terms are “sleep” and “reward,” with “anhedonia” (the inability to experience pleasure) being fairly common as well. It might deal with disorders in a broader sense, given that “mdd” (probably short for “major depressive disorder”) and “bipolar” are both common terms.

Topic 5 deals with the physiological side of depression. Several of the most common terms are related to the brain’s structure, and the preprint titles deal with it a lot – “How Stress Physically Re-shapes the Brain: Impact on Brain Cell Shapes, Numbers and Connections in Psychiatric Disorders” is a strong example, and its score in this topic is 0.95.

Topic 6 largely focuses on the specific case of loneliness and isolation, especially with respect to discrimination, COVID-19, social media, and being a student. The second-highest preprint in the topic, “Psychopathology and Perceived Discrimination Among Chinese International Students One Year into COVID-19: A Preregistered Comparative Study”, covers most of these issues.

Topic 7 has “network” as its most common term, but there doesn’t seem to be much consistency beyond that. This topic might be another case of one word with multiple definitions throwing off the analysis. Some titles from the 20 preprints with the highest topic scores:

- “The Replicability and Generalizability of Internalizing Symptom Networks Across Five Samples”

- “Quantifying the reliability and replicability of psychopathology network characteristics”

- “Objective Bayesian Edge Screening and Structure Selection for Networks of Binary Variables”

- “A Network Analysis of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and correlates in U.S. military veterans”

Topic 8 looks focused on memory and attention. “Task” having a high importance is consistent with this, since (from what I’ve read, at least) tests of memory and attention are usually called “tasks” in the literature instead.

Topic 9 is pretty clearly about COVID-19.

Topic 10 might be kind of a mixed bag, given that it seems to have some of the lowest counts for its top terms. The actual terms themselves suggest a focus on identity, and culture. Some of the preprint titles like “Loss and assimilation: Lived experiences of Brexit for British citizens living in Luxembourg” suggest this topic could describe lifestyles and life experience in general.

This topic does have a notable outlier, though. One preprint called “Psilocybin for Depression The ACE Model Manual” doesn’t match the above description very well, but the way it’s written makes it clear that it’s talking directly to the reader, and inspection of the term frequency matrix shows that it accounts for about one-fourth of the uses of the word “you” in the entire corpus. Some other high-scoring preprints in this category seem to include anecdotes from people, which frequently use “you” or “your” in their transcriptions, which may be the reason for this.

Conclusions

Several of the topics here seem to have fairly good focus. Whether a larger or smaller number is better isn’t necessarily clear – the fact that some of these topics are less focused might recommend more topics, but I feel like a few muddled topics are inevitable, given the tricky nature of natural language in general.

Also, I mentioned this in passing in the previous post, but I’ll repeat it here: There’s somewhat less focus on medications than I would have expected. I don’t know if that’s indicative of anything regarding antidepressant research, or if there’s something generating more interest in non-medication research, or if antidepressant research just ends up elsewhere.

For LDA in general, the notable outliers here are a good reminder that inspection of the texts themselves is a good check to ensure that the topics make sense. Since LDA is unsupervised and ultimately powered by a term frequency matrix, it’s possible that it could be thrown off by documents which have some grammatical quirk or repeat some bit of text over and over in some irrelevant way, like with the above outliers.